Captives, Patriots, Conscientious Objectors, Loyalists, Spies

My father’s ancestors were all more recent immigrants (They came in the 1860’s & 1880’s). These are all that I have found so far on my mom’s side (Cornett’s and Clifford’s). To put it in perspective, on that side, I would have had 16-4th great grandfathers (some were too young) and 32-5th great grandfathers…etc. So there are many possibilities, some I haven’t traced back that far, and at least one was a more recent immigrant.

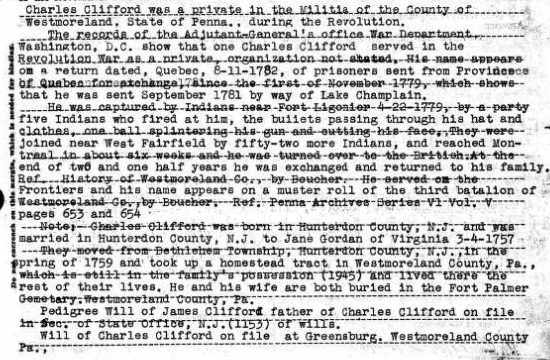

Charles Clifford (1730-1816), my 4th great grandfather, had been a Private in the Pennsylvania Militia, County of Westmoreland, during the Revolution.

John N. Boucher’s account of Charles Clifford’s capture by Seneca Indians in the “History of Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania,” pages 98-102:

Of the capture of Charles Clifford we have a very good account both by tradition and by various writings which confirm it. He resided on Mill Creek, a tributary of Loyalhanna, two and one-half miles northwest of Fort Ligonier. In winter time he and his family stayed in or near the fort, and in the early spring they resumed their work on their clearings. On April 27, 1779, he and two sons went to their land to do some work preparatory to planting their spring crops. When they reached the place of their work they could not find their horses which they had left there the day before to graze over-night. The boys set to clearing up the land and the father went to look for the horses. He first went up to some newly deadened timber tracts near the present town of Waterford, for there he had found them once before when they strayed away. Not finding them there he continued the search, and finally reached the Forbes road leading to the fort, perhaps between Waterford and the present town of Laughlinstown [present day Highway 30 generally follows the old Forbes Road in that area]. Still he could not find his horses, and so concluded to abandon the search and return to the fort by the road. He had gone down the road but a short distance until he was fired on by five Indians who were concealed behind a log lying by the wayside. None of the balls wounded him severely, though one of them splintered his gunstock and thus cut his face, which bled profusely, though it was only a flesh wound. The Indians ran up to him, wiped the blood from his face, and seemed very glad he was not injured. They told him he would make a good man for them, and that they would take him to Niagara. They took from him his hat, coat, vest, and shirt, allowing him to retain his trousers and shoes. One of the Indians cut away the brim from his hat and amused his fellows very much by wearing the crown. Another wore his shirt and another his vest. They gave him his coat to put on, but to this he objected unless they gave him his shirt also, saying he could not wear a coat without a shirt under it. But they did not take his suggestion kindly, and he was forced to submit, and told to hurry up as they must hasten on their journey.

On the long march they treated him much more kindly than one might expect. The whole race was superstitious, and when five of them shot at him at once and failed to kill him, they concluded that he had some power to ward off dangers and might be very useful to them. They did not tie his arms, as was their universal custom even with half-grown boys. At night he slept between two Indians, with a leather strap across his breast, the ends held firmly by two Indians lying on them. As soon as they lay down they slept, but Clifford had too many things to think of to sleep so readily. Gently he drew the one end of the strap from under the Indians by his side and sat up. The moon was shining bright, but there was an Indian on a log, whose turn it was to watch the camp and keep up the fire. The watch sat silent and motionless as a statue, but the prisoner knew he was awake and would probably make short work of him if he attempted to escape.

They had journeyed nearly north from where they captured him. At a point where now the village of Fairfield is located, they were joined by fifty-two other Indians, whose general trend was northward. The chief, Clifford said, had his head and arms covered with silver trinkets. They tore down fences to roast meat, but warily marched a mile or so away from the smoke to eat and prepare a place to rest over night. Clifford had great desire to see the other prisoners and to learn if his sons were among them. They had only one other prisoner, whose name was Peter Maharg [Mehargs]. [His name also appears on the list of Rebel Prisoner Returns.] When Clifford found him he was sitting on a log much dejected, too much so to reply to Clifford’s salutation. and sat his head down in perfect silence. As it was learned afterwards he had been taken the same day and while hunting his horses. He had seen the Indians before they saw him, and was making his escape, but his dog running ahead of him, came running back to his master as soon as he saw the Indians. To the Indian this was all that was necessary. Maharg was taken at once. They further scoured the northern part of the valley for prisoners or booty, but finding nothing that was not guarded they left on the third day for their home, which was near the boundary between Pennsylvania and New York, near the headwaters of the Allegheny River. They had thus journeyed about two hundred miles and killed but two people and secured but two prisoners. On their long march homeward they marched by daylight, but always camped an hour or so before sunset. Eight or ten of them guarded the prisoners while the others hunted through the woods. At the camp they generally all met about the same time, and the hunters generally brought in venison, turkey or smaller birds. After the evening meal they lay down after the manner of the first night.

After they crossed the Allegheny river the game became scarce, even a squirrel. All the party from then on suffered greatly from hunger. At one time for three days they had nothing to eat at all except the tender bark of young chestnut trees. This they cut with their tomahawks and offered it to their prisoners. Each of them refused, and received the consolation of ‘you fool; you die.’ They now sent out two swift Indians, who went ahead and in three days returned with some other Indians, among them some squaws, and who had beans, dried corn, and dried venison. They gave the prisoners a fair share of these provisions. The Indians then divided into two parties, and one of them took the dejected Maharg, while the other took Clifford. Maharg was treated most cruelly, most likely because he remained so morose and dejected, for this from the first disgusted them with him. They made him run the gauntlet, and pounded him so severely that he fell before he had passed the line. The beating that he received did not stop when he fell. He never recovered from it, but bore marks from it on his body when he was laid down many years afterwards in his last sleep. Running the gauntlet consisted in passing between two lines of Indians stationed about six feet apart, and the lines the same distance apart. The Indians were provided with clubs, and each had a right to hit the prisoner as he passed. If the prisoner was strong he could sometimes escaped pretty well, but it was at best a most painful and dangerous ordeal.

Clifford had been from the first under an Indian who claimed him as his servant. After he had become somewhat accustomed to traveling without a shirt, his Indian gave him a shirt and hat. The shirt was covered with blood and had two bullet holes in it, and was probably taken from one of the men whom they had killed. Before he was taken prisoner, Clifford while working among the bushes had badly snagged his foot, and this without care became very painful, and the long marches had brought about inflammation and swelling. On showing it to his particular Indian guardian, he examined it very carefully and then went to a wild cherry tree with his tomahawk and procured some of the inner bark. This he boiled in a small pot and made syrup with which he bathed the foot, and after laying the boiled bark on the wound bound it up with pieces of a shirt. It very rapidly reduced the swelling and allayed the pain.

They kept Clifford six weeks and then delivered him to the British at Montreal. He learned much about their customs and curious manners, and never failed to interest his hearers by a narration of his experiences and observations among them. He saw four prisoners running the gauntlet, one of whom was killed. At another time, when a horse had kicked a boy, the animal was at once shot by the father of the lad, and the Indians ate the meat, which they thought delicious.

At Montreal [actually at Fort Chambly, which at that time was about 20 miles east of Montreal, Quebec, on the Richelieu River, a tributary of the St. Lawrence River] he grew in favor with the officers of the garrison and fared much better than most prisoners. He procured from one officer a pocket compass which he gave to a prisoner named James Flock, who escaped, and by the aid of the compass, made his way back to Westmoreland county through an almost endless wilderness, finally arriving at his home long after his friends had given him up for dead. Clifford was in Montreal two years and a half when he was exchanged. He then made his way back to Ligonier valley, having been gone three years.240 [See end note #240 for an interesting addendum to Charles returning home.]

Charles lived to be an old man and was respected by all who knew him. He is buried in the old Fort Palmer cemetery, one of the oldest graveyards in the county. He died in 1816. He was a soldier of the Revolution.

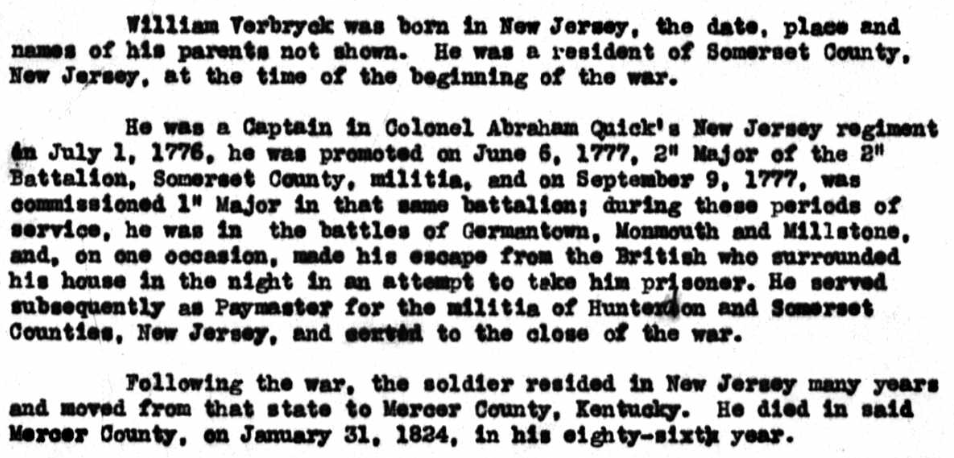

William Verbryck (1737-1824), my 4th great grandfather:

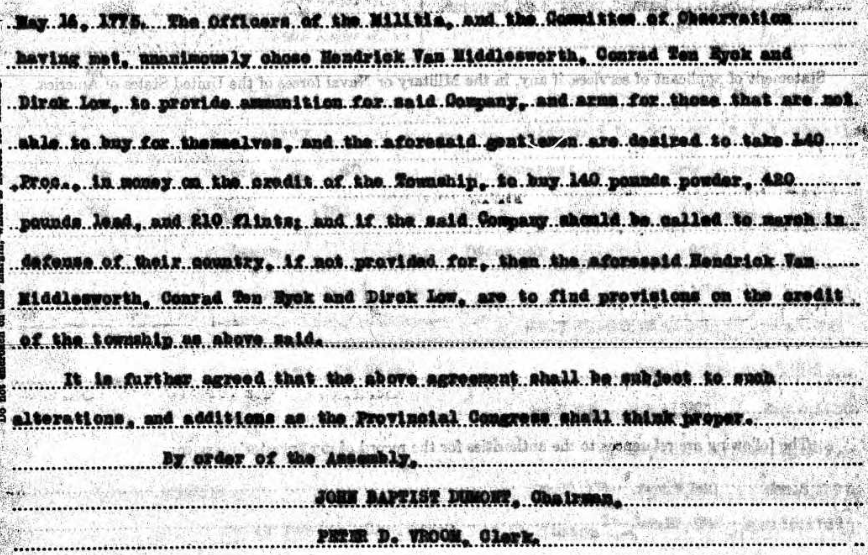

Dirck (Derrick) Low (1717-1802), my 5th great grandfather:

Solomon (Zalomon) Decker (1722-78), my 6th great grandfather– a patriot giving information to American soldiers regarding Tories and Indians. He was born and died in New York.

Abraham Hildebrand (1748-1833), my 4th great grandfather:

Judge Abraham Hildebrand was a German Baptist/Dunkard. It is guessed that Judge Abraham understood German as he bought his land (1776) Conestoga Twp. Lancaster Co., PA from Johannes Neitig witnessed by George Graff; the last two signed in German. The deed was written in English. We know that Judge Abraham could read and write English by the later deeds he signed and by his capacity as judge.

The 1777 non-associators record meant Judge Hildebrand was not in the Revolutionary War and chose to be non-associated. This agrees with his religious beliefs as a Dunkard – a Peace church. He was living in Lampeter Twp, Lancaster Co., Pa in 1777.

George Weimer ( 1762-1826), my 4th great grandfather–This appears to only be a reference to a book in the Pennsylvania Archives in which he was listed and where he was buried:

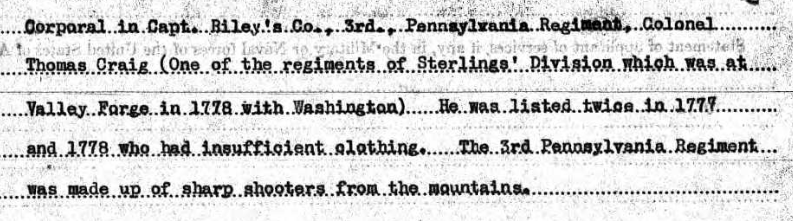

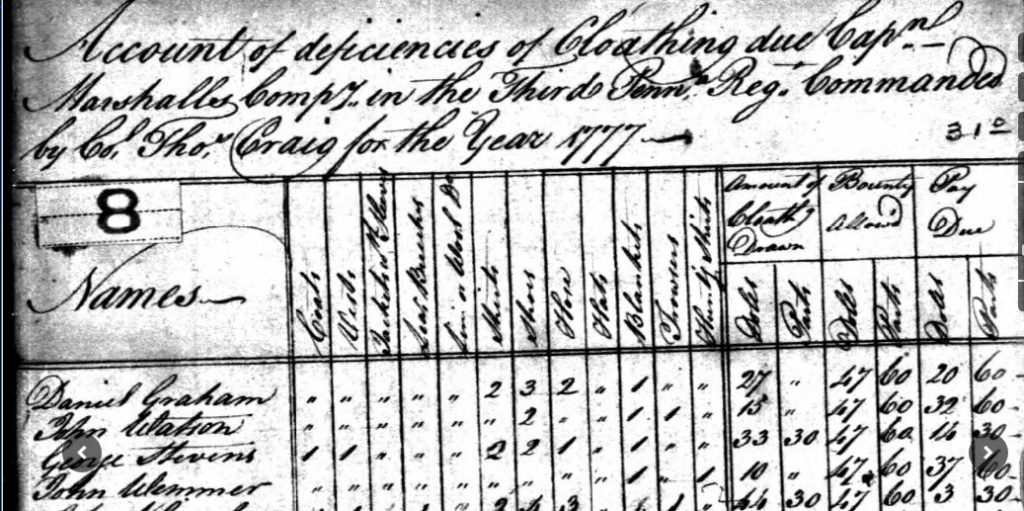

John Dewatt Weimer (1740 –1831), my 5th great grandfather, George Weimer’s father. He is the one I had discovered had been listed with “Insuffient clothing” at Valley Forge. His name is sometimes recorded as Wimmer, Wymer or Wemmer. “According to other researchers John’s Company marched on Phildelphia, in protest, over not being paid in over a year. Along the way they were intercepted by a British detachment that offered them twice the pay if they would come over to the British side. The Company refused.”

“Brothers John, Frederick, and Martin Weimer emigrated from Dortmund, Germany in 1760. They landed in Baltimore, Maryland, and later settled in Pennsylvania. All three were Revolutionary War soldiers…He served as a corporal in Captain John Riley’s Co., Third Pennsylvania Continental Line in 1778-79 which was at Valley Forge with George Washington. After the Revolution, John, his wife Susanna (born 5-7-1741, died 1-27-1831) and their family settled in Somerset County where he was granted 336 acres of bounty land in Milford Township. He received title to his land on Feb. 26, 1788 and named it Prospect Hill.”–Taken from page 177 of “Down the Road of Our Past” Book III Rockwood Area historical & Genealogical Society

David Cornutt (1750-1847), my 5th great grandfather and probably his brother in Grayson County, Virginia:

Phillip Russell, Sr. (1745-1792), my 6th great grandfather appears to have been a Loyalist:

According to the work of Ms. Linda Cuff-Cornett, Philip Russell, Sr., was the son of William Russell, Jr., and Rebecca Louise Witherden. (Presumably, they were also the parents of the other Russell brothers, Samuel and William.) She further states that William Russell, Jr., son of Lord William Russell, Sr., was born May 29, 1721, in County Kent, England and died in 1784 in Surry County, Virginia. Evidently, William, Jr., emigrated to Virginia and Philip, Sr., was born in Surry County.

It is almost certain that the Russell brothers [Phillip and Samuel] were Loyalists during the Revolutionary War. (This should not be surprising since during the American Revolution, as in any civil war, families were often divided in their loyalties) At this time, they appear to have been living in northwestern North Carolina. This presumption is supported by records of the County Court of Wilkes County, North Carolina, which indicate that Philip Russell was ordered into the custody of the county sheriff in June of 1778 and was present in insolvent’s court (either as insolvent or as a committee member) on March 5, 1779. Moreover, it is well known from contemporary sources that many of the inhabitants of this region were sympathetic to the Crown. Furthermore, the presumption that Philip and Samuel Russell were Tories is further supported by the work of Murtie June Clark in Loyalists in the Southern Campaign in the Revolutionary War, which is cited by Shirley Ramos and Patricia Kratz, in which Private Philip Russell is listed as having been a member of Captain John Wormley’s Company of the Royal North Carolina Regiment between October 24 and December 24, 1781. Apparently, he was captured by colonial forces since it is indicated elsewhere that he was held as a prisoner of war by the rebels. In addition, Private Samuel Russell was listed in the pay abstract for Colonel Robert Ballingall’s Regiment appearing in a Certification for Service of the Colleton County, South Carolina, Militia. In any case, following the Revolutionary War, Philip Russell, Sr., along with his brother, Samuel, evidently settled in southwestern Virginia, in the area later organized as Grayson County. There they established families although, perhaps, they may have already married in either North Carolina or Virginia. According to Ramos and Kratz, a record exists which indicates that Philip Russell, Sr., died without property in Wythe County, Virginia, on January 23, 1792. (Grayson County was formally established by the Virginia General Assembly on November 7, 1792, from a part of Wythe County.) In contrast, other researchers indicate that he subsequently lived in Grayson County and died about 1807. However, there is no evidence from tax lists or other civil records that Philip Russell, Sr., and his son Philip, Jr., were both alive in Grayson County during the first decade of the nineteeth century. Therefore, the earlier date seems more likely. Moreover, the clear implication that Philip, Sr., was a pauper at the time of his death is, perhaps, consistent with confiscation of his property by victorious opponents of his Loyalist sympathies.

Paul Patrick (1730-1799), my 7th great grandfather:

The American Militia and Regulars company of Capt Paul Patrick in June 1780 belonged to the Regiment of Col. Elisha Isaacs.

They rendezvoused at Hamblins Old Store and joined General Rutherford at Salisbury and then joined the main army under General Gates at the mouth of Rocky River.

At this River they had a battle with the British and the Tories.

The army then marched to the road that leads from North Carolina to Camden and was in another battle with the British and Tories. General Gates was defeated in this battle.

Jonathan Stamper Sr. (1719-1799), my 6th great grandfather:

Jonathan was Surrey County [Virginia] Constable. During the American Revolution, he supplied the American forces with horses and provisions. Cited from Find a Grave

Edmund Hodges (1709-1782), my 6th Great Grandfather.

-furnished supplies for the soldiers during the Revolutionary War. (Virginia)

William Woodrum Jr. (1759-1841), my 4th great grandfather.

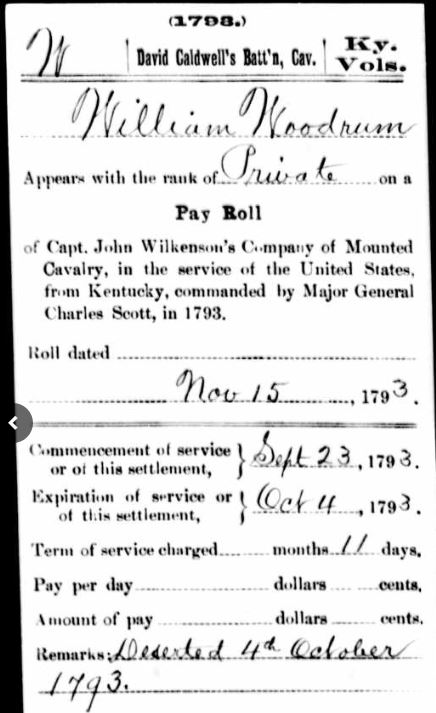

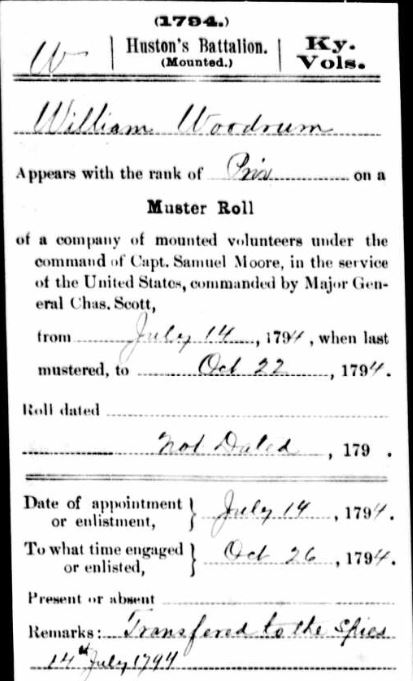

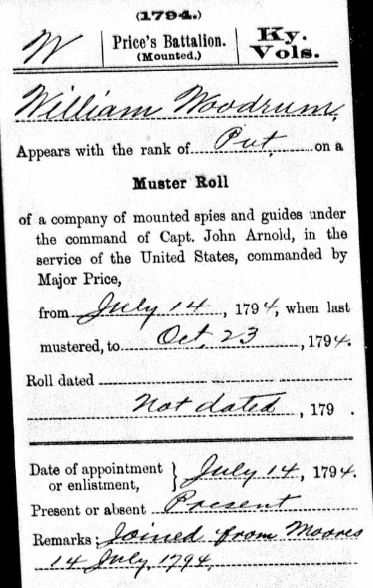

William fought in the Rev. War and as a private in David Caldwell’s Batt’s Cav Ky. Vols . 1793 and apparently deserted. Later he returned as a private in Huston’s Battalion Mounted. Ky. Vols 1794 and transferred to “Arnold’s Spies” in Price’s Battalion mounted Ky. Vols 1794.

His Father-in-law:

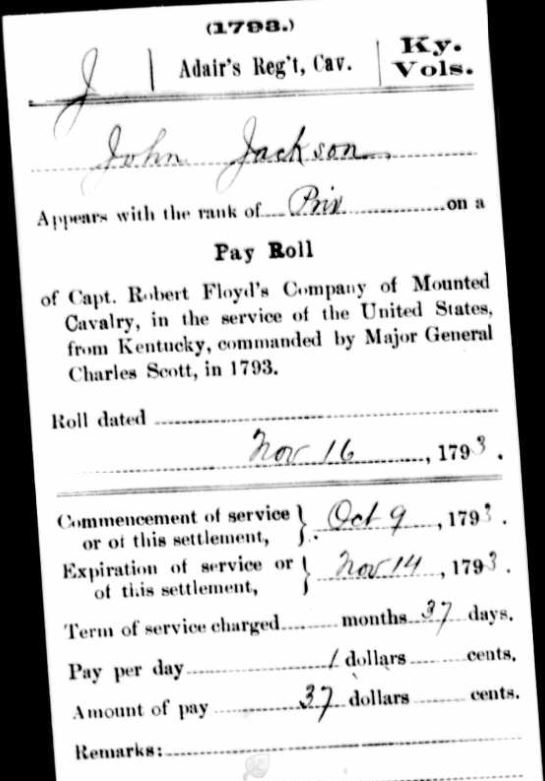

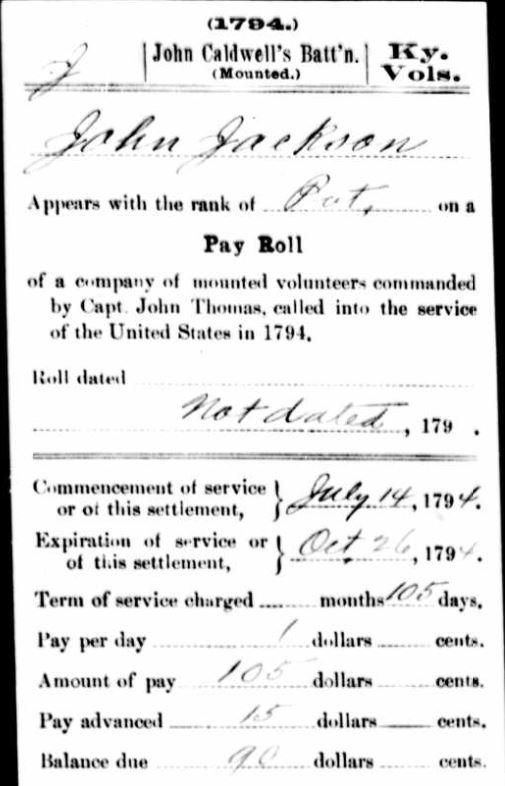

John Jackson (1739-1821), my 5th great grandfather may have been a private in Adair’s Regiment under the command of Capt. Robert Floyd. He also may have served for 37 days in 1873 then 195 days in 1784 in John Caldwell’s Battalion in 1874 under Capt. James Thomas. There is another John Jackson that was Killed in action 10 Aug 1794 in Conn’s Battalion. Since it is a fairly common name, it is difficult to tell for sure.

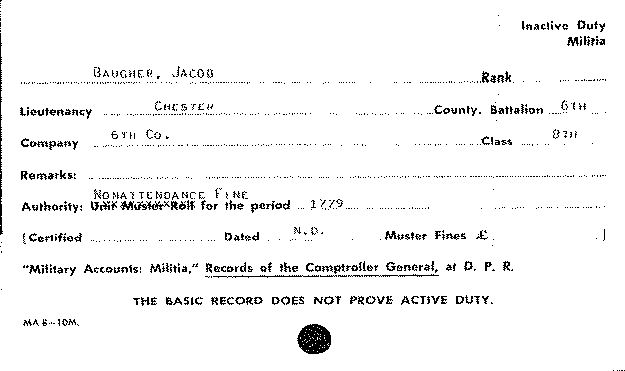

John Jacob Baugher (1760-1832), my 5th great grandfather.

“Information from Joyce Brown has John Jacob Baugher as having served with Chester County, Pennsylvania militia in Revolution.”–Thornbury Company of Militia (Pennsylvania Archives, Vol 5. pg. 795)